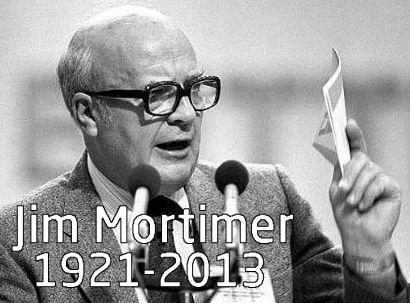

Pundits and commentators of a New Labour tendency have not been kind to Jim Mortimer, General Secretary of the Labour Party during its trough of depression in the first half of the 1980s. He is, in particular, held responsible for the election manifesto of 1983, memorably described by Gerald Kaufman as “the longest suicide note in history.”

Pundits and commentators of a New Labour tendency have not been kind to Jim Mortimer, General Secretary of the Labour Party during its trough of depression in the first half of the 1980s. He is, in particular, held responsible for the election manifesto of 1983, memorably described by Gerald Kaufman as “the longest suicide note in history.”

At the fag-end of his tenure I was elected to the constituency section of the National Executive Committee, and I have a far kinder assessment. He was a thoughtful and intellectual trade unionist, straight as a die; at 61, instead of enjoying well-earned retirement he agreed to become General Secretary of an impecunious and troubled Party in those turbulent political times at the request of the new Labour leader. Michael Foot. Mortimer and his partner Pat, later his wife, were of deeply held socialist opinions. In his attitudes to the issues of the day he chimed with the concerns of Party workers equally concerned about subjects such as nuclear weapons and workers’ rights.

If he had retired then he would have been remembered as a serious academic who had given his life to the trade unions, written and lectured with authority on union affairs and been relatively uncontroversial. In fact he was to be one of the party’s most controversial General Secretaries.

Mortimer was contemptuous of “spin”. His background was one in which politicians and unions spoke as plainly as they could. He was unapologetic in helping to put forward Labour’s aims. The 1983 election campaign was difficult since left and right could not decide what they wanted.

Mortimer did make what was perhaps a colossal boob, but it was understandable at the time. Early in the campaign he replied to a hostile question from a tabloid journalist by saying that the Party “had full confidence” in its leader. I saw the film of this incident which showed Mortimer as soon as he’d made his announcement, looking bewildered at the journalists’ excited reaction. He hadn’t ticked on to the fact that his words might cause the electorate to question Foot’s leadership and Labour’s unity of purpose. Mortimer was not streetwise, but blaming him for the election defeat in the wake of the triumphalism of the Falklands War, which he had passionately opposed, would be unfair.

He was born in 1921, the son of a disabled newsagent eking out a living in Bradford. His father was a member of the Socialist Labour Parties, the British branch of the Industrial Workers of the World, and worked closely with stalwarts of the Left such as John Cryer, the father of Bob Cryer, a minister in the Wilson government.

From his parents Mortimer inherited a feeling for the importance of international socialist solidarity. As a young shipfitter he was in a reserved occupation; his interest in union affairs secured him a place at Ruskin College at the end of the war. At 25 he worked for the TUC economic department and was picked as a full-time official in 1948 by his union, the Draughtsmen’s and Allied Technicians Association, whom he served until 1968, when he became a director of the then flourishing London Cooperative Society, until 1971; for seven years he was chairman of ACAS, which settled the most thorny industrial disputes.

Mortimer played an important part, from 1971-74, on the Armed Forces pay review body. Perhaps he was appointed in the expectation that as a left-winger with pacifist tendencies he would push for pay restraint; in fact he believed service personnel merited a proper reward even if their country was asking them to do something he thought should not be done.

A well-organised person, he found time to make a considerable contribution to the industrial literature of the day. His History of the Association of Engineering and Shipbuilding Draughtsmen (1960) was perhaps the first union history written by a working leader. In 1965 he combined with the ebullient Clive Jenkins to publish British Trade Unions Today and the influential The Kind of Laws the Unions Ought to Want, in 1968. If the line they proposed had been adopted I doubt there would have been the difficulties following In Place of Strife.

Between 1973 and 1993 he published the History of the Boilermakers Society in three volumes. Academia recognised the seriousness of his scholarship: he became a Visiting Fellow to the Administrative Staff College at Henley (1976-82) and Senior Visiting Fellow to Bradford University (1977-82) who gave him an honorary DLitt. He also became Visiting Professor at Imperial College and Ward-Perkins Resident Fellow at Pembroke College Oxford. His autobiography A Life on the Left (1999) and The Formation of the Labour Party, Lessons for Today are worth reading for any student of modern British political history.

Mortimer remained General Secretary until 1985, and as a member of the Finance and General Purposes Committee of the National Executive Committee I know it was he who staved off bankruptcy. He remained active in the union movement and was one of six Manufacturing Science Finance (MSF) members who made a legal challenge to Labour’s disqualification of London MSF votes in the mayoral candidate selection process of 2000. The courts found in Labour’s favour since London MSF had not paid its party dues for three years. Mortimer and five colleagues were ordered to pay costs.

Mortimer acted out of a concern for doing right in the Party. In my last conversation with him he expressed his dismay at how the Party conference had become a rally, discussion dampened to the point of extinction. He was proud to be “Old Labour” and believed people would only really work for a party if they believed they had some influence in its decision-making.

Tam Dalyell

James Edward Mortimer, trade union official, politician and writer: born Bradford 12 January 1921; official, Draughtsman and Allied Technicians Association (General Secretary 1958-68); General Secretary, Labour Party 1982-1985; married firstly Renee Horton (deceased; two sons, one daughter), secondly Pat Mortimer; died Portsmouth 23 April 2013.

Originally published by The Independent