We reproduce below Labour CND Chair Carol Turner’s tribute to Alice Mahon, former MP for Halifax and Vice President of CND

The death on xmas morning of Alice Mahon, Labour MP for Halifax 1987 to 2005, is a sad loss for the labour movement and for all those of us who knew her. There are few like Alice in the House of Commons nowadays – an MP who remained outspokenly committed to peace, socialism, and internationalism. She will be very missed by those of us who share those values.

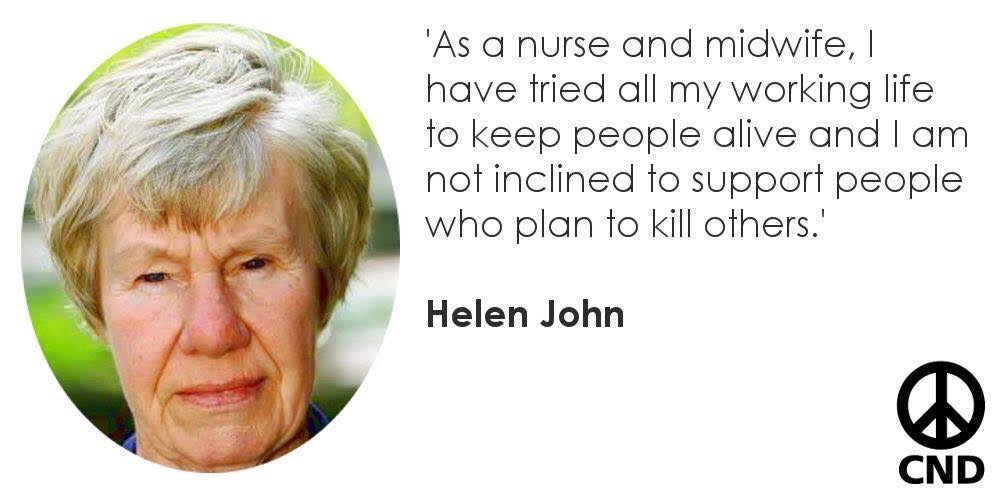

Alice was a member of the Socialist Campaign Group of Labour MPs, and an avid Morning Star reader. She was a feminist, hounded by the anti-abortion lobby during general elections, a former nurse and NUPE shop steward who held the NHS to be Britain’s most popular institution and was scandalised and ashamed when New Labour supported its partial privatisation.

Alice was proud of her West Yorkshire constituency and its working class history, and angry that successive government failed to provide the economic support the area needed and deserved. She was an anti-racist who loved that some of her grandchildren shared an African-Caribbean as well as a Yorkshire heritage.

A staunch supporter of the Good Friday peace process, Alice was an internationalist who campaigned for Palestine and for many people and liberation movements who found themselves on the wrong side of western imperialism.

Peace was central to Alice’s values, her opposition to militarism was unbending. A lifelong opponent of nuclear weapons, she was a Vice President of CND and a patron of Stop the War at the time of her death.

I met her in person for the first time shortly after her election to parliament when she spoke at a Labour CND annual conference in Manchester Town Hall, We were friends from then on, campaigning for peace and against wars together for over 40 years. At the end of the 1990s, Alice became co-chair of Labour CND with Jeremy Corbyn.

In 1990 she was one of the first MPs to join the Committee to Stop War in the Gulf, set up by CND in anticipation of the invasion which came in February 1991. She was horrified when Tony Blair supported the 2003 invasion of Iraq. As well as taking part in Stop the War activities, set up Iraq Liaison to campaign against the war amongst all the political parties in parliament.

Alice tabled an Early Day Motion which brought together the biggest show of parliamentary opposition to the war. EDM 927 was signed by 162 MPs – LibDems, Plaid Cymru and Scottish Nationalist as well as many of her Labour colleagues and including four ex-ministers.

In one of her regular news releases at the time, Alice said of Blair: ‘The Prime Minister has failed miserably to make a case for military action… Briefings by ministers are pathetic – lightweight statements of belief with no facts whatsoever about the actual situation.’

Alice was also a well-respected UK member of the Nato Parliamentary Assembly, even chairing one of its sub-committees for a time. A fierce opponent of its military missions, her involvement in its parliamentary structures didn’t stop her from attacking Nato. Sadly, this would likely see her removed from today’s Parliamentary Labour Party.

As with Iraq, so with former Yugoslavia. Alice and I set up the Committee for Peace in the Balkans at outbreak of civil war in the 1990s. She was one of a very few western parliamentarians who opposed western intervention – believing it had little to do with protecting Yugoslav citizens and anticipating the likely outcome.

Despite media vilification, she remained adamantly opposed to Nato bombing campaigns and visited Yugoslavia several times during the 1999 bombing, one of the very few western politicians to do so.

She spent time on the round-the-clock picket of Downing Street set up by Yugoslav expats during the 1999 bombardment, visited the Chinese Embassy in London to express condolences when Nato bombed its Belgrade Embassy, and travelled to the ICTY (International Criminal Tribunal on Yugslavia) in the Hague to lobby chief prosecutor Carla Del Ponte.

Shortly after she left parliament, Alice resigned from the Labour Party, disgusted by New Labour war-mongering. She rejoined when Jeremy Corbyn was elected leader. On her death he Alice was ‘an utterly brilliant working-class campaigner, one of one of my best comrades in parliament’.

Outspoken on politics, on a personal level Alice was respectful of colleagues and opponents alike, treating all equally regardless of rank or status. Her warm manner veiled some sharp insights which poked out from time to time in a surprisingly acerbic humour – like when she’s quipped to Blair on the floor of the Commons during an Iraq debate: ‘Who’s next, North Korea?’

Alice was a kind and generous human being. It won her respect and many friends, and together with her hard work on behalf of her constituency, made for a growing majority at each election. A walk around the town centre with her would usually take considerably longer than it should, as she stopped every 100 yards or so to exchange a few words with the dozens of Haligonians who greeted her.

Alice loved Halifax. She fought hard for her constituents first as a Calderdale councillor then as an MP. She lived in a modest bungalow in Northowram village, a couple of miles from Halifax town centre and not much further from where she was born and grew up.

Back from London most weekends to be with her family, she and Tony, her husband and best friend who died less than a year before her, spent evenings in their local chatting to mates and telling stories about the weird and woolly doings of parliament.

Alice was an MP whose political commitment and loyalty to friends, comrades, and community deserves to be an example to every one of today’s parliamentarians and would-be parliamentarians of tomorrow. She was, however, much more than that – someone who worked hard at living a life in line with her socialist principles.

* This obituary first appeared in the Morning Star 15-01-23

CND‘s tribute to Alice Mahon

Jeremy Corbyn‘s tribute to Alice Mahon